The first point is that I live in London. Sometimes it’s known as a Concrete Jungle. The second is that I brought up my children here, and I regarded it as my duty to wring as much joy from the jungle as I could, when they were small. Hence, Cockroach Day at the Science Museum (we wore special carapaces). Hence, burials in a Viking ceremony at the British Museum. Loads of this stuff was free, and it was fun, in a rogue way.

I have been tainted by my own parenting, and now still reject a loose evening on my own in London. This is why, dear reader, when my husband was out with his choir, I found myself in a cinema this week watching this documentary about concrete. If you can get to a screening, I recommend it.

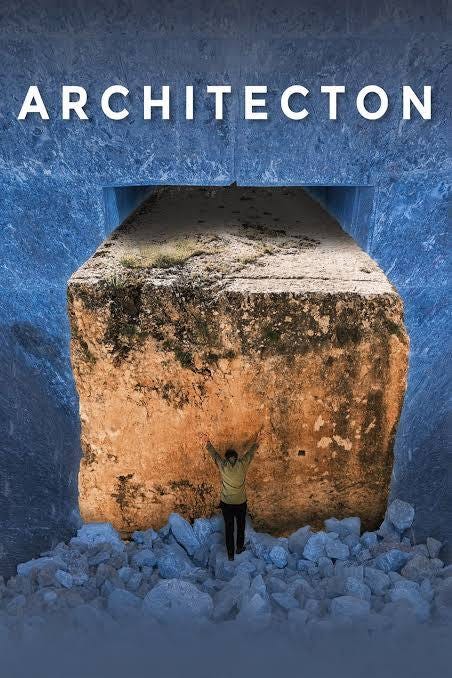

Architecton, which is currently on cinematic release, and on the BFI player from March 10, is about sustainability, not just concrete, yet the making, transporting and use of the stuff provides something of a line through it. Concrete is apparently the most used substance in the world, second only to water.

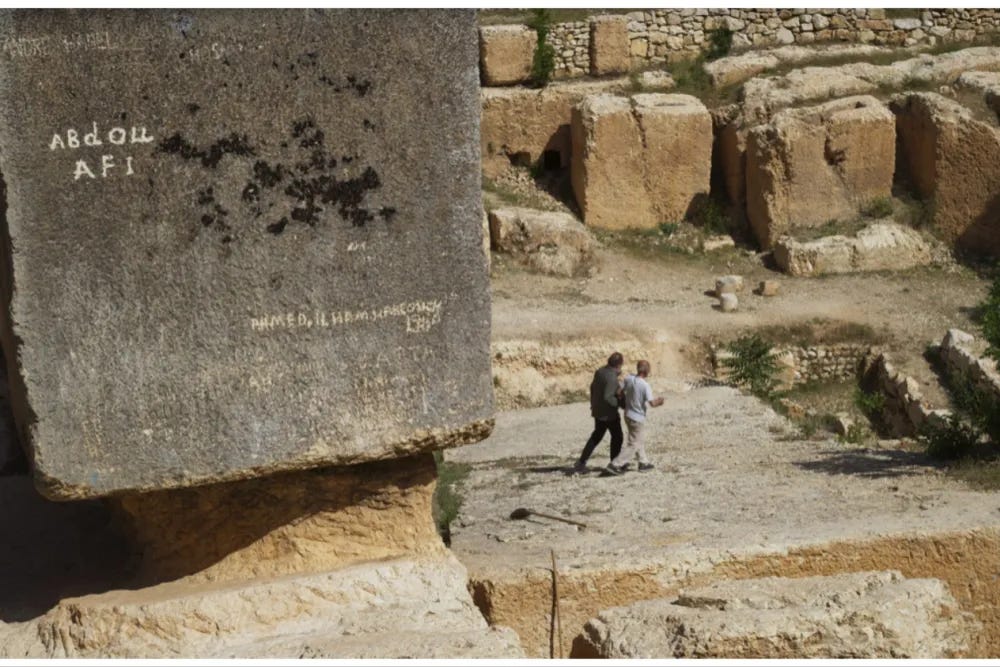

It starts with several astonishing minutes on what I thought at first was an avalanche, but transpires is quarry mining. Tens of thousands of huge rocks and stones cascade in slow motion down a steep incline, falling and bursting into shattered pieces. There is no voice over, just ominous music. This pouring of bouncing stones goes on and on in an almost hypnotic manner. We then see the giant quarry, carved into the mountain as if it was a colossal amphitheatre.

The giant stone quarry from Architecton

During the course of the 90 minute film, which was made by the award-winning Russian director Victor Kossakovsky, we see the whole process from the explosions in the quarry onwards. Drone cameras almost lovingly film the vast machines which shudder rocks into smaller stones, and then grind them into powder. We see a thousand-carriage train winding through a desert, each cart filled with stones. Fresh concrete squirts out of a machine, like cake frosting, but that’s not the end. Kossakovsky wants to show us abandoned modern slabs, buildings with their rusty reinforcements sticking out of them like spinal cords, houses in Turkey laid waste by the 2023 earthquake, and shattered, bombed communities in Ukraine, with mountains of rubble being endlessly pushed off to unlovely landfill.

The production and despoilation of concrete is contrasted against a lengthy sequence where on a snowy day, the Italian architect Michele De Lucchi guides two builders to create a modest circle of stones in his garden, within which he will plant grass. On its completion, it will be closed off to humans. Only dogs and horses can enter it.

Michele De Lucchi (seated) in his garden

The film lingers on concrete’s ancestor, stone, in the form of classical temples and buildings, some still standing. Their preservation makes an elegant argument against the concrete ruins. One particular sequence is devoted to the ancient temple of Baalbek in Lebanon, which contains the second largest cut piece of stone in the world.

The megalith from Baalbek weighs 1,000 tonnes. How it was cut and transported is unclear.

There is not much voice over in the film, but the message is clear. You are left meditating on waste and bad planning. Why do we blow up the countryside in order to build so many things which contain in-built obsolesence? The Romans didn’t. The Victorians definitely didn’t. De Lucchi rails against a skyscraper he has been commissioned to design in Milan, which he says will only be standing for 40 years.

The Festival of Britain; a London view now consigned to the archive

The film made rather an elegant pendant to Simon Schama’s current arts survey on BBC 2, The Story of us, which showed how little time it took Churchill to demand the demolition of most of the 1951 Festival of Britain’s domes and pavilions on the South Bank, probably because it had been commissioned by his rival and post-War predecessor Clement Atlee. All the buildings bar The Festival Hall, were pulled down in the same year that they were opened, and the site left derelict for a decade. It seems a style of modern leaders, this habit of unpicking whatever project the person before directed, be it the Paris Climate Agreement, or the Festival of Britain. Imagine if successive Plantagenet kings had felt that way about Westminster Abbey, which took 400 years to build.

So feeling rather down about concrete, I went to the 90th birthday celebrations of the artist David Hepher whose new show Tower Blocks has just opened at Flowers in Hackney. Hepher mostly paints vast art works of a certain estate in Camberwell, South London, and these are what is on show. The tower blocks are made of concrete. So is the art. Hepher actually paints on concrete; he sprays it over vast canvasses and depicts not only buildings, but also the surrounding trees and glass and graffiti, on the unyielding surface. The overall effect is a tense play between hard and soft, translucent and reflecting. If you look closely at the picture below, there is a tiny rendition of Constable’s iconic Hay Wain in the middle. Hepher has rechristened it in suitable South London argot.

David Hepher, Hey Wayne on the Meath Estate (2019)

After he had blown out his candles, and we had all sung to him, Hepher took charge of a giant chocolate cake. I told him I had just been to see a film about concrete, and he seemed gratified.

While there, I bumped into my friend the poet and writer Sue Hubbard, who urged me to go to see Breaking Lines at the Estorick Collection in Islington. “There is an exhibition on Dom Sylvester Houedard there at the moment. You know, Houedard. One of the masters of concrete poetry”.

Dom Sylvester Houedard, Benedictine monk and master of concrete poetry

It has become something of a themed week. Next stop: The Brutalist!

I agree about the sustainability issue. Concrete has a full life of about fifty years. It is a miracle post war buildings in Europe are still standing. I live in an apartment building constructed in the late seventies, an old one by concrete standards, but the whole city of Athens is built like that!

One reason for this choice of material, is the earthquake factor. In the Mediterranean, the size of earthquakes far exceeds those in the North. Houses in Britain, especially the common semi, would not be able to withstand such magnitudes without the assistance of a steel/or concrete frame.

I must see this - it’s showing in Leeds at Hyde Park Cinema…On the day I’m in London!