Five of the Best - The Early Renaissance

Emotion, daring, realism - the five artists who kicked it all off

The Renaissance. It’s such a loaded word, and it comes with huge expectations of knowledge. And the subsets can be confusing. There’s “Renaissance Man”, but no Renaissance Woman, the “High Renaissance” but no Low Renaissance, and so on.

Five of the Best aims to cast a bit of light on this, because it is worth illuminating. The whole era is radical, beautiful and exciting, and once you are on firm footing with the Renaissance, its dramatis personae and some dates, the entire Western canon makes sense. It’s worth getting to grips with.

So here, is my Five of the Best in the Early Renaissance. The Early Renaissance is usually, but not always, focused on Italy, and this is where we will be for all five art works. I could have chosen twenty five, but here is what I feel to be the core. These five are mesmerizing, and powerful, and act together as a strong indication for what happens next. Buckle up!

1. Lamentation, 1305, Giotto di Bondone

One of the key tenets of the Renaissance is the focus on the human, on realism and on emotions. This tiny fresco by Giotto, just one panel of a huge cycle in the Scrovegni Chapel, Padua, has all of these things.

Christ has been taken down from the Cross, and is being cradled in the arms of his mother. You can tell by the limpness of his arms, and the fact that someone is holding his lolling head, and the still nature of his bare feet, that he is dead.

The monumental psychological effect of this rings across the painting in several ways. The small angels above and Jesus’ followers below manifest a dramatic, public display of grief as if on stage, all pulling of hair and wringing of hands.

At the heart of the painting, indicated by not only the direction of all gazes, but also the descending stone wall, is the intimate moment between Mary and Jesus. Mary puts her face close to the face of her son, her eyes swollen with crying. Look at how her hands make a beautiful necklace of shapes around his neck, and how her knee supports his body.

But the figures which make this painting a true outlier, almost a modern work, are the two nearest to us. We are not allowed to see their faces. We just see the volume of their bodies. They are hunched, almost rocking in sorrow. They are not interested in us. Their world has stopped. What inspired Giotto to put these two in? They are crucial to the notion of privacy and shock which pervades the entire piece.

For Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea, standing on the right hand side, however, business needs to continue. They are upset, but they are men of the world. “What happens now?” one seems to be saying, almost (but not quite, because that would seem rude), turning to the other.

This was painted in 1305, with egg white on fresh plaster. Probably took Giotto a morning. Astounding. 1305!

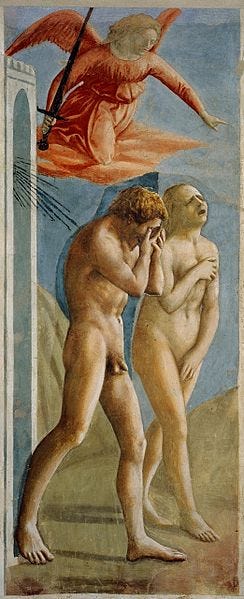

2. Adam and Eve, 1425, Masaccio

Over 100 years after Giotto (and others) threw down the gauntlet of depicting emotion, volume, and realism in painting, Masaccio was the one who took up the challenge.

This is his devastating fresco in the tiny Brancacci Chapel of the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine, in Florence. It depicts the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden. They have been flung out via the gate on the left hand side, by a furious angel who hastens up behind them wielding a flaming sword.

Eve is open in her shock and sadness, covering herself in shame, crying out. Adam is tightly bound up, hiding his face, his stomach muscles clenched. Stomach muscles! On a naked man, realistically depicted and occupying space and volume on a wall! The pair even cast shadows. This is a real couple, stumbling towards an uncertain future.

With this painting, achieved when he was only in his twenties, Masaccio fires the starting pistol for the Renaissance. It is our great luck that he worked in the city of Florence, a young, wealthy and ambitious place which acted as a magnet not only for gifted artists, but for patrons looking for something to demonstrate their wealth and power. One needed the other. And so a movement began. Could Michaelangelo have happened without Masaccio? Unlikely.

3. David, 1440, Donatello

This gorgeous, sexy work which stands in Florence’s Bargello sculpture museum, is the first freestanding male nude made since the Classical era of the Romans and Greeks. This is why it is heralded as a key work of the Early Renaissance, as it takes the style of the classical world and looks forward to a new beginning, reviving those ideals in art. David might well be a figure from The Bible but he stands like a classical hero, in contrapposto, which is when a figure stands with weight on one leg and a curve goes up the whole body. This was a defining characteristic of classical sculpture as it made the subject look dynamic, almost as if you were to look away, and then look back, and find that the person had moved. As if David was a real young man.

Donatello depicts David just after he has killed the giant Goliath. He stands with his foot casually on Goliath’s head, which he has just severed using the giant’s huge sword. David is holding the sword, and wearing only a pair of boots and a hat topped with laurel, the classical symbol of the victor.

It’s about more, of course. David was the symbol of Florence herself, the young upstart against the giant Rome, and this image represents Florence cheekily demonstrating its ascendence over the older Italian city. It was commissioned from Donatello by the Medici family, the famous banking dynasty who took Florence to greatness and (fortunately for us) used artists to help their glorification.

4. Baptism of Christ, c1449, Piero della Francesca

Commissioned by a Tuscan monastery, this masterpiece of the Early Renaissance is now in the National Gallery, London.

Why does it look so calm, so clear, and so peaceful? Because Piero was a master of classical geometry. Not for him the anxious Gothic manner of stuffing loads of people into a tiny spot and let them struggle out of it. Here, everyone has their own certain space and position. They stand solidly in a real place. One even leans languidly against another. The anatomy is perfect. Jesus is reliably muscular as the hero of the story.

Try putting a piece of tracing paper over the image. You can draw an equilateral triangle from the dove (symbol of God) to each bottom corner of the picture. You can draw a vertical line down the middle and find Christ who is being baptised by John, in the centre. You can draw a horizontal line across the heads of the angels and the two main protagonists and find it goes through them all.

However this picture would be too right, and rather chilly, I think, without the delightful human touch of the neophyte (someone about to be baptised) on the right. Piero has definitely been down to the local swimming baths and watched someone pulling off their shirt. Of course he has. This is why this picture smacks of real life.

5. Dome of Florence Cathedral, 1436, Brunelleschi

Look at this wonderful dome, floating above Florence. The symbol of the city but also of a new way of looking, and of creating, art. Brunelleschi makes up the triumvirate of the Early Renaissance in Florence alongside Masaccio (painting) and Donatello (sculpture). His architecture made a decisive break with the Gothic buildings of the past, and pointed to a way forward using Classical references, in this case the dome.

The monumental Dome of Florence Cathedral is still the largest masonry vault in the world. In the world! Six hundred years ago! How did he achieve it? By going to Rome and studying how the Romans did it, and then rather than slavishly copying the ruins that he found, simply applied their maths to the fifteenth-century cathedral whose dome he had to build. It was a new style, on the springboard of the old. This is why we call it the Renaissance (reborn). No plans or sketches remain, but Brunelleschi’s feat of engineering continues to inspire and amaze today. Without this dome, there would be no St Peter’s. There would be no St Paul’s. There would be no modern buildings with their classical arrangements, their arches and columns.

============================================================================

Thank you so much, dear paid subscribers. This week’s Five of the Best takes us away from galleries and dives into a bit of art history, because once you know even a little about the history and the order of what happened, and the key works, your enjoyment of galleries is expanded a thousand times.

If you enjoyed this, do press the LIKE button. And see you on Thursday for the straightforward Arts Stack.

wonderful

made my day !