Get children into art. Kids into museums. Forget about encouraging old people, or even middle aged people. Or hope that parents might lead the way. Children need to be put in front of art works, in order for them to ‘engage’, and it’s up to arts companies themselves to do it. This central plank of cultural policy is now so embedded that no arts organisation, certainly none with even the tiniest dash of Arts Council money, dares question it. In this mission, arts organisations are helped by a huge array of trusts, foundations, and well-meaning billionaires, all trying to do the same thing.

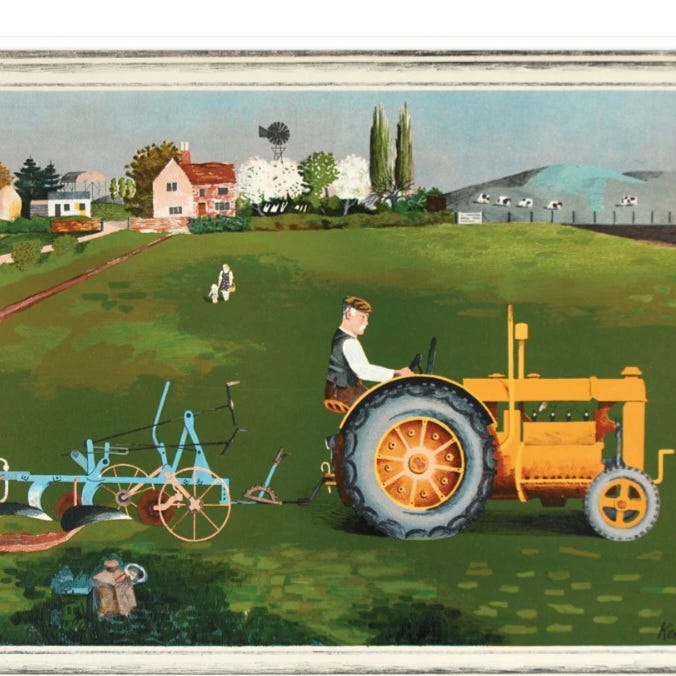

Tractor (detail), by Kenneth Rowntree

But there is another way. And this way is best expressed via the vision of one person, a pilot called Derek Rawnsley, who had it just before the Second World War. His idea, was simple, but dauntingly brilliant, and its final iteration is currently on show and on sale at the Goldmark Gallery in Uppingham.

Where do young children go everyday? Why, they go to school (or at least, most of them do). Alright, take the art out of galleries and put it into schools. Normal, state schools. Primary schools. That was Rawnsley’s idea. If you are walking, or running past the same picture every day, you become familiar with it. If you are daydreaming in a maths lesson, you look at what is on the walls. If you are bored in Spelling, ditto. This is how billboard advertising works. And in 1935, Derek Rawnsley believed it was how fine art could work.

Rawnsley wasn’t an artist, a curator or a politican. He was however a dashing character, and full of derring-do. Dashing characters who have nothing to do with art, but are happy with risk, sometimes are exactly what the often extremely risk-averse art world needs, and Rawnsley was one such person. He once broke a world record by flying a Tiger Moth from Australia to, er, Abingdon.

Derek and Brenda Rawnsley on their wedding day, 1941

His simple but brilliant notion was to reproduce contemporary prints - not Old Masters, but the art of the day - and hire them out to primary schools. The art works were printed on thin paper, so they could be pasted directly up onto the walls. The schools didn’t need to pay much in order to hire the works. And what artists he chose! Only the best. The catalogue reads like a mid-century roll call of the best in the world, which is who they were. School Prints sounds like something from a dream, or a CS Lewis plot, but it was real, and a huge success. Within two years Rawnsley had a catalogue of nearly 150 prints which he had chosen, and which were loaned out to primary schools across England. But that was just the beginning.

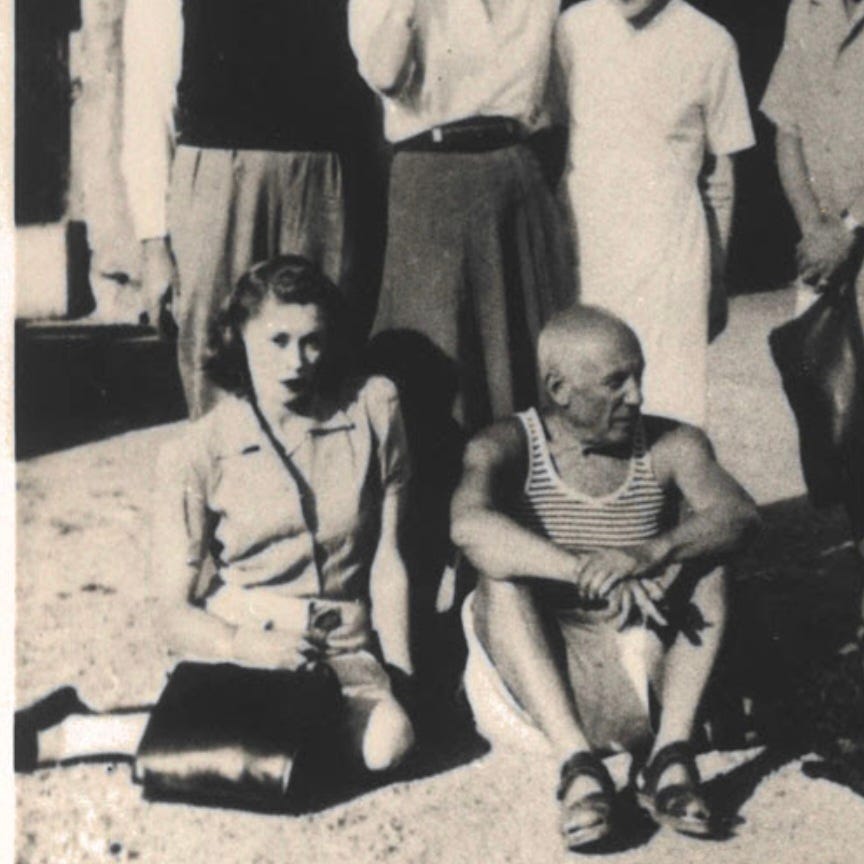

In 1939, he met Brenda. They were married in 1941, but on the eve of their wedding night, Rawnsley was posted to Cairo, and remained in active service. He was killed in 1943. His widow Brenda Rawnsley was, if anything, more visionary than her remarkable husband. She had no knowledge of the arts or, frankly, the printing world. However, she took on the School Prints scheme in memory of her husband, and extended it far beyond its original parameters.

This time, the schools could buy the prints, so they were in the building in perpetuity. How much more dynamic a memorial for anyone than having a name carved onto a stone block! Thanks to Brenda, Derek Rawnsley’s vision lived on in the minds of small children, thousands of them.

Rather than using extant images, Brenda decided now was the time to commission original art works, and again went to the best of the lot; Matisse, Moore, Dufy, Braque. What a moment to do such a thing for primary schools! This was the mid-century moment, remember, and she made the most of it. There is a picture of her hanging out with Picasso in France, who also accepted a commission.

Brenda Rawnsley and Picasso in the South of France

Why should small children have anything but the best? There were restrictions; six colours only could be used, but the subject matter could be anything the artist wanted, as long as the image was suitable for primary schools. No proscribed ideas or policy here. The free imagination of the artist was what Brenda Rawnsley was interested in. She was aided by an advisory panel under the leadership of critic Herbert Read. Cardboard and paper were strictly rationed after the war. Brenda went to the black market for both, to supply the demand from schools, which was huge. Thousands of primary schools signed up for works of luminous, wonderful art. A fish swimming under the beak of a bird, by Braque; a pack of playing cards by Fernand Leger; The Dancer, by Matisse. These pieces would sometimes have been the first art works ever put before a child; they are not only wonderful, but they speak directly of their time; they are overwhelmingly contemporary.

The artists themselves were no less keen than Rawnsley, even the grand ones; there is a picture of Georges Braque preparing his lithograph “The Bird”; Brenda Rawnsley had letters from Henri Matisse and Raoul Dufy discussing their commissions.

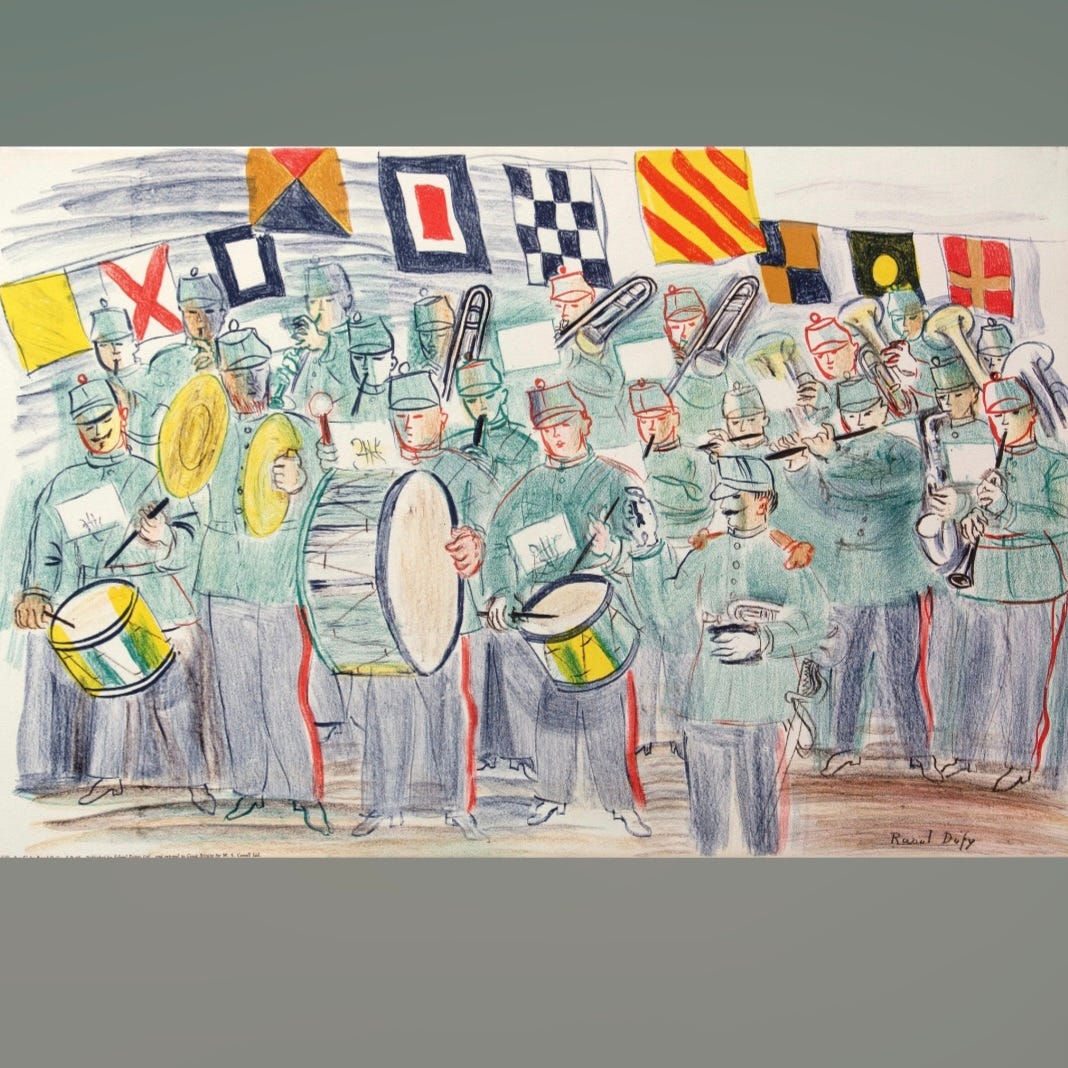

The Band, by Raoul Dufy

“I am very happy with your opinion on my “Military Music” print,” writes Dufy, after receiving his commission for The Band, “and I hope that the public, above all children at school, will share it.” Matisse is a bit more straightforward. “I can let you know that I have received the sum of £100 for the sale of my lithograph.” Henry Moore seems a little bit anxious about the reception of his print, Sculptural Objects. “I am so glad you like the picture,” he writes on March 3, 1949. “I hope it won’t be a disappointment when it it printed.”

24 prints were eventually commissioned, and almost all produced as auto-lithographs, which means the design was drawn directly onto the stone by the artist. It is as close to drawing and painting as possible, since there is no interference from machines or assistants. (This was a pre-Warhol era, remember.) The artists include the ones already mentioned, plus giants such as Edward Ardizzone, John Nash, and Barbara Jones. Of the whole series, Goldmark Gallery suggests it is LS Lowry’s Punch and Judy which was the most loved.

Punch and Judy (detail) by L.S. Lowry

Very few of the original prints produced by the Baynard Press, still remain, perhaps unsurprisingly, since they were taped, tacked or glued onto classroom walls well over half a century ago, and used very thin paper. The Goldmark Gallery has however acquired some of the last caches of lithographs in pristine condition, and from it has produced a set of prints which you can buy. They honour the memory of Derek and Brenda Rawnsley, not least because they are not wildly expensive, ranging from just over £100 to around £2,500. It’s strangely moving to look at them and imagine what went through the mind of a schoolchild, in those hard years immediately after the War, looking at one of these during a lesson, or fleetingly glancing at it on the way to lunch.

That's an amazing story- I didn't know anything about this initiative. I remember a poster of Hunters in the Snow by Bruegel up in my primary school assembly hall in the 1970s and it always puzzled and annoyed me, it seemed too bland and dull to be a famous painting, I found the way the hunters were frozen would worry me. But I must have spent hours gazing at it and when I finally saw the original in Vienna it had a huge emotional impact on me!