This week’s plan was to write about membership of big arts bodies, and whether it’s worth shelling out for a Member’s Card. But I ditched this yesterday after I read the clarion call of ‘veteran’ arts hack Richard Morrison and his masterplan for making the arts more accessible. For those not behind the Times pay wall, I’ll explain. Firstly, it has nothing to do with giving the (underfunded) arts world more money. Even with a change of government, and even if the Arts Council of England changes its policies, he admits there won’t be any more money. His idea?

Shake up the school curriculum “so that every child benefits from a rich, inspiring immersion in the arts”. If you do this, he suggests, you won’t have to insist on special engagement and inclusion policies within arts organisations, because young people will already be engaged and included, and if you feel a sense of belonging when you are young, you will feel this way for life. Even though he says it will take a generation to achieve this, I agree.

I think about my History of Art A Level classes at school. Firstly, we looked at slides of Early Renaissance masterpieces in the Chemistry lab (the only classroom with a projector). Then, we looked at the pictures in books. I remember tracing an equilateral triangle and a circle onto Piero della Francesca’s Baptism of Christ (above) and seeing how the artist conveyed perfection because he had fitted all the key people within perfect geometry. After this, we went to the National Gallery, and saw it.

Thanks to this course, I will never be lost in any art gallery exhibiting Early Renaissance treasures. Many private schools, of which mine was one, offer History of Art A Level. Of this country’s 4000 state secondary schools, fewer than eight offer History of Art A Level. Eight! History of art is the history of thinking, of politics, of life. Not in the view of our schools. The AQA board dropped A level History of Art in 2018. Given the wealth of art easily available in British national collections across the UK, this is a disgrace. Unsurprisingly, the Courtauld Institute, which offers degrees in History of Art, has almost no state school take-up in its undergraduate body. As Jonathan Jones railed in the Guardian a few years ago, “Art history has become an obscurantist, elitist subject.”

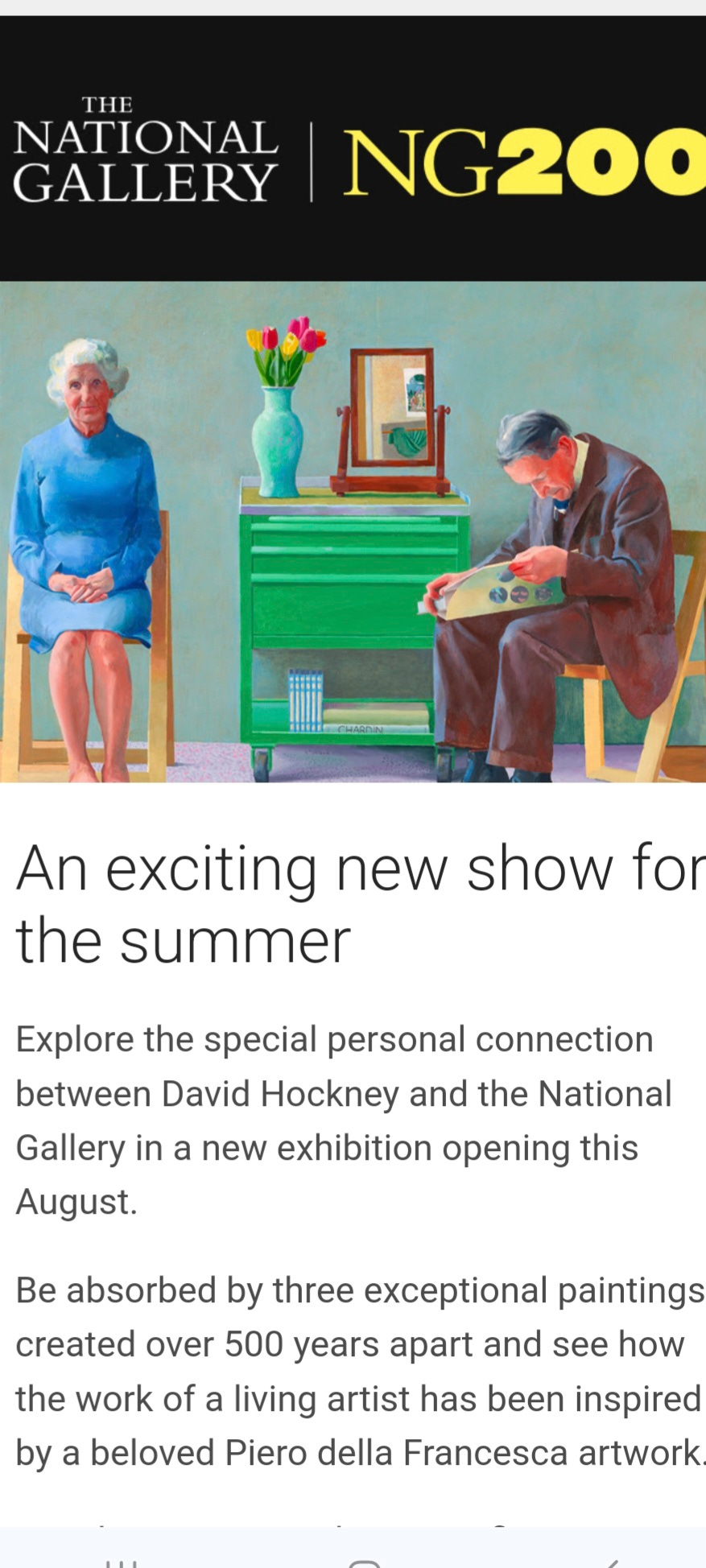

The National Gallery, standard-bearer for this “obscurantist, elitist subject,” which is free for all to visit, occupies a building at the metaphorical and actual heart of our capital. As I am a Member, it emailed me yesterday with information about “an exciting new show for the summer”.

Hockney and Piero: a Longer Look, which is free to visit, will exhibit two works by David Hockney and a painting by Piero della Francesca which inspired him. Unsurprisingly, this painting is the Baptism of Christ.

I don’t want to pour cold water on the National Gallery’s programme, and I salute its mission to connect living artists with the canon. I am sure this will be an amazing exhibition, but I predict there will be a sum total of zero young people at it who are not part of some officially organised tour, or have not studied History of Art, even though it involves our most famous living artist and one of the absolute masterpieces of the Italian Renaissance, and even though it costs nothing to visit.

It’s not just the study of the Renaissance. Many state schools have dialled down music lessons, choirs, orchestras, drama and dance; the sort of soft, non-academic ‘extras’ that wealthy private schools and grammar schools deliver so well to their cohorts. The sort of things which adults spend time engaged in, via the creative industries but also as amateurs, and from which they derive great meaning, status, fulfilment and (sometimes) a significant salary. Underfunded state schools, obliged to teach a narrow curriculum obsessed with STEM, don’t have time and don’t have money to look this way. The result of this is that generations of young people are leaving school without a properly embedded knowledge of the arts.

There are valiant efforts. Music Masters energetically brings orchestral instruments and teaching into state schools, as does Music in Secondary Schools Trust. The remarkable History of Art Link Up connects a small number of state school students across the UK into collections, teaches art history and arranges History of Art exams for them so they can evidence their learning for higher education. But these are tiny charities whose impact can only be measured in modest numbers.

I once ran an equally tiny charity called Children and the Arts. We paid arts organisations across the UK to connect with schools in their area, and bring them to their buildings two or three times a year. Small children could feel a local gallery or museum was ‘theirs’. It ground to a halt. Why? No money. No time. A dwindling ability for the schools to free up classes. No pressure within the schools to make time to free up classes, because the subjects were not on the curriculum.

Arts bodies work hard to make their work accessible. But starting from ground zero is tough. You need infrastructure. You need properly paid and trained staff; teachers, really, and projects which will encourage parents and carers to bring their children in. All of this distracts arts bodies from their main mission, “It is not the LSO’s responsibility to educate children. It is the government’s job to start educating children and creating not only talent for the future, but audiences,” fumed Sir Antonio Pappano, chief conductor of the London Symphony Orchestra, last month.

Why do we have such wonderful institutions if wave after wave of young people are not being encouraged to go to them? The art galleries of this country hold precious treasures owned by the nation; they are our treasures, but they are not regarded as such by our schools and exam boards. If I hadn’t sat in that Chemistry lab all those years ago, and hadn’t been taught by my charismatic teacher Barbara Todd how to really look at Piero’s balanced, lucent Baptism of Christ, this summer’s show at the National Gallery wouldn’t matter, and I wouldn’t go to it. But I did, and I will.

Well … I champion what the fab leadership team does at Music Masters, above all a very impactful use of limited resources. I had free instrumental lessons in my state school and it’s life changing.

This is a really important piece. Thank you Rosie - and also for the recognition of what Music Masters does in primary schools!